Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Important People in the Political Struggle for Aboriginal Rights

| |||||||

1927 - 1984 | |||||||

|

|||||||

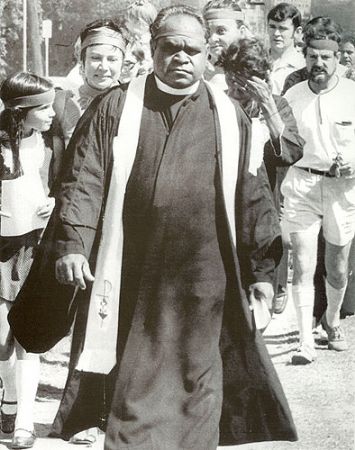

Don Brady (1927-1984)

Methodist pastor and Aboriginal leader, was born on 20 April 1927 at Palm Island Settlement, North Queensland, second child of Queensland-born parents Jim Brady, stockman, and his wife Grace, formerly Edmond, née Creed. Don was of Kuku Yalanji descent; his tribal name was Kuanji. As a boy at Palm Island he learned to perform traditional dances and to play the didgeridoo. He worked as a farm labourer and was a professional tent boxer for three years; in practice sessions he sparred with Jack Hassen, among others. A Christian from an early age, he trained as a missionary at the Men’s Native Workers Training College of the Aborigines Inland Mission of Australia, at Karuah, near Newcastle, New South Wales, and graduated on 10 December 1949. After another year of study he was appointed to Brewarrina, but soon transferred to Walcha, and in 1952 to Moree. On 26 January that year he married a fellow missionary, Aileen Muriel Willis, at the AIM Church, Cherbourg, Queensland.

In 1962 Brady moved to Brisbane and, after attending the Methodist Training College and Bible School, began work as a lay pastor in July 1964 with the West End Methodist Mission, ministering to urban-dwelling Aborigines. A self-confessed former alcoholic, he was known as the `punching parson’ because of his ability to handle homeless inebriates frequenting Musgrave Park, South Brisbane. In 1965 he expanded his ministry to include the Christian Community Centre, based at the Leichhardt Street Methodist Church, Spring Hill. Providing not only spiritual guidance but also welfare assistance, the centre catered for some three thousand people. Brady established a sports club in a vacant church building in Upper Clifton Terrace, Red Hill, and set up a gymnasium where he instructed young men in boxing. Keen to foster in Aboriginal children an appreciation of their cultural heritage, he taught songs and dances, and formed the Yelangi dance group, whose performances he accompanied on the didgeridoo. He also showed local people how to make traditional artefacts.

Awarded a Churchill fellowship in 1968, Brady travelled to the United States of America to study the `integration of indigenous people’. On his return he became active in the struggle for rights for Aborigines. Joining other Aboriginal militants, including Denis Walker and Cheryl Buchanan, he helped to form the Brisbane Tribal Council (from 1970 the National Tribal Council) to help Indigenous people to establish their own identity and to preserve their culture. In February 1970 he was elected founding vice-president of the Aboriginal Publications Foundation. On 12 April he led a silent street march to mourn the loss of Aborigines who died in defence of their country, and to demonstrate against `the disruption of the aboriginal way of life by the white invasion’. After the protesters arrived at the Leichhardt Street church Kath Walker (later known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal) addressed them outside, and Brady conducted a service inside in memory of those `thousands of our people who have died because of ignorance’. Aware that the procession had come to the attention of the police traffic and special branches, he assured the group of about sixty that this was a one-off event, and should be seen as similar to the annual Anzac Day remembrance service. He argued that the march was not intended as a demonstration of Black Power but rather as an assertion of Aboriginal rights.

In November 1971 Brady participated in a street march protesting against a bill before the Queensland parliament that extended governmental control of tribal and reserve councils. He and Denis Walker were arrested and charged with assaulting police. Using the media to highlight inequities in housing and employment opportunities, he inspired other Aboriginal people to join the battle for social justice. He encouraged young Queensland Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders to protest at the Aboriginal `tent embassy’ set up outside Parliament House, Canberra, in January 1972. In July that year the board of the Brisbane Central Methodist Mission, which was reorganising the Christian Community Centre, asked for Brady’s resignation. Following negotiations, he was released from responsibilities for spiritual care and in September was appointed to a new position, subsidised by the Commonwealth government, as liaison officer looking after the physical, social and political welfare of Aboriginal people. The centre, now independent of the mission, continued to use the Leichhardt Street premises.

Brady died of pneumonia complicating hypertensive cerebrovascular disease on 27 January 1984 in South Brisbane and was buried with Uniting Church forms in Mount Gravatt cemetery. He was survived by his wife, four sons and two daughters; two children predeceased him. More than five hundred people gathered at Musgrave Park to mourn his passing. Praising his leadership, Rev. Charles Harris described him as `the Martin Luther King of the Aboriginal race’. His peers hailed him as a civil rights advocate who gave Aboriginal people a sense of pride and taught them to fight for their rights.

Select Bibliography

W. McNally, Goodbye Dreamtime (1973) | |||||||