Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Heroes in The Struggle for Justice Important People in the Political Struggle for Aboriginal Rights

| ||||

1943 - 2010 | ||||

|

||||

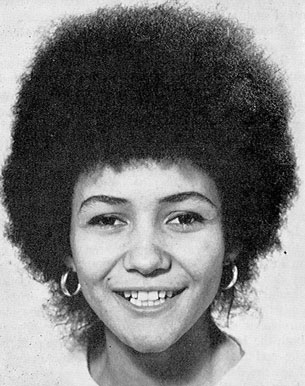

Roberta "Bobbi" Sykes

Dr Roberta Sykes, a self-described chameleon who defied conventions to become a well-known activist for indigenous rights as well as a poet and author of renown, died at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney after failing to recover from a stroke suffered eight years ago. She was 67.

Widely know as Bobbi Sykes in her early activist days, she was the first black Australian to attend Harvard University in the US. She graduated in the 1980s with a doctorate in education.

She was awarded the prestigious university's highest academic award, which usually goes to students from the schools of law or medicine, and taught there briefly.

Advertisement: Story continues below

Sykes went on to be awarded the Australian Human Rights Medal in 1994 for her tireless work in advocating for the civil and political rights of indigenous Australians.

She first became an activist in the lead-up to the landmark 1967 referendum that proposed to include Aboriginal people in the national census and to allow the federal government to make laws for Aboriginal people.

However, it wasn't until she moved to Sydney in the early 1970s that she became deeply involved in the emerging ''black power'' movement and in 1972 was one of the founders of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on the lawns of old Parliament House in Canberra.

She became the first secretary at the embassy and was among those protesters arrested. Sykes's activism led ASIO to regard her as a threat to national security and spooks kept close track of her. It can now be revealed that a Sydney academic who has prepared a bibliography - she authored 10 books, among them two on poetry - was given access to three volumes of information collected on Sykes by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

Ironically, for a time her work in this sphere attracted criticism from some Aboriginal leaders, who felt aggrieved that she had used the Aboriginal snake motif in her acclaimed autobiographical trilogy, Snake Dreaming - made up of Snake Cradle (1997), Snake Dancing (1998) and Snake Circle (2000) - when she was not an Aboriginal.

But Sykes identified fully with indigenous people and causes, subjected as she was to racism while growing up in north Queensland - including its most vile form.

At age 17, she was pack-raped by four white men, one of whom shouted as he was being sentenced to jail: ''What the hell, she's just an Abo; she's just a f---ing boong.''

Born Roberta Barkley Patterson in Townsville, she was raised by her mother, Rachel Patterson, who made sure the rapists were brought to trial. While her daughter claimed not to know anything about her father, Rachel revealed he was an African-American soldier, Robert Barkley, a master-sergeant in the US Army during World War II.

Sykes left school at age 14 and worked as a shop assistant and then nurse's assistant in Townsville before moving to Brisbane. Another move followed, to Sydney in the mid-1960s, where she took the stage name Opal Stone and performed as a striptease dancer at the Pink Pussycat nightclub in Kings Cross.

At about this time she met an English migrant, Howard Sykes, a house painter, and they married. She already had a son, Russel, who was born when she was 17; a daughter, Naomi, was born during the marriage, which ended in 1971.

Sykes's private life was complex: on the one hand she easily made numerous enduring friends, yet this wasn't reflected in the partners she chose over the years.

She began writing in the 1970s and in a 10-year period as a freelance writer, contributed many more articles on Aboriginal disadvantage and indigenous politics to various outlets, as well as film reviews and poetry.

She also worked as the education and publicity officer for the newly established Aboriginal Medical Service in Redfern. From 1975 to 1980, Sykes was an adviser on Aboriginal health and education to the NSW Health Commission and her first book of poetry, Love Poems and Other Revolutionary Acts, was published in 1979.

In 1981, she ghosted the award-winning autobiography of well-known NSW indigenous social worker, Mum (Shirl) Smith. That year, aged 38, Sykes went off to Harvard with her young daughter in tow and completed her master's degree in a year, followed by a PhD in Aboriginal education in a further two years. Her son Russel, now a psychologist, initially stayed in Sydney and looked after the family home but then joined his mother at Harvard, where he, too, studied for a year.

She returned to Australia from Harvard determined to create more educational opportunities for others and devoted herself to being a proactive voice for indigenous Australians.

Despite her achievement at Harvard, which considered her worthy of an academic appointment, she found it difficult to attract a similar appointment in Australia until she gained a creative writing appointment at Macquarie University. She went on to be a consultant to several government departments, including the NSW Department of Corrective Services and the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody.

Sykes's honesty, bravery, charm and charisma touched many. One of these, David Bardas, the former owner of the Sportsgirl stores, has offered to commission a portrait of Sykes to be hung in the National Portrait Gallery to honour her place in Australian history.

Bardas's late wife, Sandra (nee Smorgon), also an early member of the Black Women's Action in Education Foundation, befriended Sykes in the 1970s.

Together they were involved in the Greenhill's Foundation op-shop and, with the late Hyllus Maris, encouraged the founding of Worawa Aboriginal College, Victoria's only independent institution for indigenous education.

Bardas recalled visiting Sykes on the campus at Harvard: ''We were staying at the nearby Ritz Carlton Hotel and Bobbi thought it was very funny when we were refused entry to the bar, because Sandra was wearing jeans and not because she [Sykes] was an unwelcome black woman.''

Sykes suffered a stroke at her unit in Redfern in November 2002 but was not found until the next day, when she failed to make an appointment.

Her son, Russel, said she was immensely frustrated to be left paralysed on one side and unable to walk.

She is survived by Russel, daughter Naomi and grandchildren Lauren, Mason and Chez.

by Gerry Carman | ||||