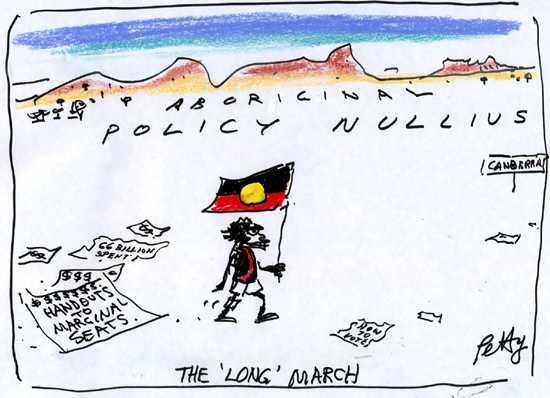

'Give us some hope'Source: The Age December 4 2004 A 300-kilometre walk. A handshake with the Prime Minister. Was Michael Long's trek to Canberra more than a gesture? Michael Gordon reports on the political impact of a footballer's simple plea.

|

|

|

Even before he rested his blistered feet and sat down with John

Howard yesterday, Michael Long had achieved what a federal election

campaign had palpably failed to do. He had reactivated the national

debate on the plight of indigenous Australians. He has also

engineered what had seemed inconceivable: the first meeting

in seven years between the Prime Minister and the man who is

regarded as the father of reconciliation, Pat Dodson. Almost as remarkably, he had brought a tear to the eye of Dodson's brother Michael, an advocate for the indigenous cause who is not prone to public displays of emotion. "We've been sweeping these problems as a nation under the carpet,'' Michael Dodson remarked after the meeting. "Michael Long has ripped that carpet bare.'' The former footballer set off almost two weeks

ago, "blackfella-style'', to walk 658kilometres to Canberra (he

stopped early when Howard agreed to meet him). Long wanted to

highlight how bad things really are in indigenous Australia. Four

years previously, he had likened Howard to the "cold-hearted

pricks'' who stole both his parents. That was in early 2000, when a

Government submission asserted that there was no stolen generation,

that the proportion of indigenous children who were separated was

no more than 10 per cent and that this group included those

removed Long replied with a searing open letter to Howard that told his own traumatic story and concluded: "Mr Howard, I am part of the stolen generation. It's like dropping a rock in a pool of water and it has a rippling effect, so don't tell me it affects 10 per cent. No amount of money can replace what your Government has done to my family.'' Just as Howard apologised two days later to those offended by the submission, Long subsequently apologised for likening Howard to the "cold-hearted pricks'' who implemented the policy of forced removal. The Long Walk was made more poignant by the backdrop of simmering tensions on Palm Island (see story page 6) and Goondiwindi, where episodes of violence have demonstrated how far Australia really is from being a reconciled nation. To outsiders, Long's gesture may have seemed a little pointless. Indeed, an editorial in The Australian called it "a long march that can solve nothing''. After all, Long's stated aim was to have a meeting with the Prime Minister, yet there was never any doubt that Howard would see him. Not only that, he had been offered, and had rejected, a seat on the Government's advisory body on Aboriginal affairs, the National Indigenous Council. But to dismiss the Long Walk as symbolic and even shallow is to underestimate Long's frustration and grief, and to misunderstand his wider purpose: to ensure that the voices of elders like Pat Dodson are heard as the Government embarks on a new policy to end passive welfare and address disadvantage in Aboriginal communities. It is also to ignore the lack of trust that is a legacy of Howard's almost nine years in power - the product of decisions to wind back land rights, to deny the existence of the stolen generation, to reject all the key recommendations of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation (including for an apology for past injustices and negotiations towards a treaty) and, finally, to abolish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, the body that was to deliver self-determination to indigenous Australia. Now, there is a new plain-speaking, energetic minister in Amanda Vanstone and a new, even radical, approach to what Howard has always called "practical reconciliation''. The aim is to reduce duplication by "mainstreaming'' service delivery and to dramatically expand the principle of mutual obli gation so that, for instance, there could be no funds for pools in Aboriginal communities unless children attend school. As Vanstone told the Senate this week: "It's all about sharing responsibility, showing respect to each other and allowing local people to shape their future.'' The approach picks up many of the points raised by Cape York indigenous leader Noel Pearson, who has been campaigning for years to end the passive welfare that has rendered too many communities dysfunctional and racked by domestic violence, substance abuse and suicide. But Pearson, like Long, declined an invitation to take a seat on the Government's new advisory body. He had proposed that the chairperson of the council be elected, with other members appointed by the chairperson and the Federal Government. The proposal was rejected. Pearson has no problem with the quality or the commitment of those, like Sue Gordon, who did accept appointments, but he believes the body is flawed because of the lack of authority that stems from the selection process and the advisory role. Now, with the Government's re-election and the distinct prospect of it being in power for another six years, Long's aim is to ensure that the most respected indigenous voices, like those of the Dodsons, Pearson, Western Australia's Peter Yu, central Australia's David Ross and Melbourne University's Marcia Langton, are heard. The clear signal from the meeting is that he has succeeded, though these are very early days. Pat Dodson was the unwitting catalyst for the walk when, at Long's invitation, he and his brother Michael addressed a camp of indigenous AFL players in Broome last month on the importance of leadership. Long was moved when Pat Dodson told the story of Rosa Parks, the black woman who refused to give up her seat for a white man on an Alabama bus in 1955, propelling the civil rights movement in that country. Shortly after the camp, Long rang Dodson and told him that "enough was enough"; he was walking to Canberra to talk to Howard and wanted Dodson and his brother to be there for the meeting. "He's a pretty committed man, pretty determined," Dodson said this week. "I think he feels that gulf between the Government and what he considers the senior leadership of his people. Of course I said I'd come along." So, too, did Michael Dodson and the respected Victorian Paul Briggs. Pat Dodson is a strong supporter of the Pearson strategy for ending passive welfare and giving communities a stake in the mainstream economy. He also backs the Government's philosophy of mutual obligation, but warns of the potential for disaster if it is driven by bureaucrats, without proper engagement of indigenous communities. Dodson also believes it is time for the Government to talk seriously with those leaders who were sidelined after the Government's election in 1996, those who were considered close to the Keating government and who remain committed to some form of settlement between black and white Australia. "If he (Howard) is prepared to accept the kind of position Michael is putting and enter a different relationship, I think there is a whole body of us who would be prepared to do that, without compromising the principles we believe in," Dodson says. "We don't come as Laborites or anything else. We come as people who are equally concerned about the need to create a better life for Aboriginal people and ensure that the Aboriginal child has got the same life expectancy as his or her counterpart in the broader community." (Indigenous males can now expect to live 56.3 years, compared with 77 years for all males. Indigenous female life expectancy is 62.8 years compared with 82.4 years.) Vanstone insists the door will be open to all, but says the NIC will be the pre-eminent indigenous source of advice to the Government. "We've got together a group of indigenous people who are specialists in areas that we think are going to help us," she says. At the council's first meeting, beginning next Wednesday, the 14 members will be asked their opinion of the Government's priorities of making communities safer and ending passive welfare. While Vanstone says the aim will be to give communities a "real voice" in tackling their problems and setting goals, she baulks at the word self-determination. "Communities get the chance to shape the Australian Government contribution to their community, instead of that being decided in Canberra." The plan is for indigenous co-ordination centres to replace ATSIC offices and combine all services so that communities can have a single agreement instead of dozens of them. "Shared responsibility agreements" will commit communities to perform agreed tasks in return for infrastructure spending. It sounds sensible, but there are concerns about whether the bureaucrats or the communities will have the capacity to make agreements that result in better outcomes, whether over-zealous bureaucrats will be paternalistic and whether existing programs that are working could be discarded during the transition. Then there is the question of resources, and the strong view of many who have worked in the area that more needs to be invested. "If they're committed to having better outcomes, they have to be honest about the need for additional resources," says Olga Havnen, who has been involved in successful community development and nutrition programs around Katherine in the Northern Territory. There is another concern, too. The concentration on disadvantage and ending passive welfare means there is less focus on the need for non-indigenous Australians to regain the momentum towards reconciliation and on the progress that is being made. As Reconciliation Australia chief executive Mike Lynskey puts it: "We tend to blame Aboriginal people if things go wrong. We've got to get out of that habit. We've got to admit our own failures as a general community." Long, through his work with the AFL in helping indigenous players, can claim part of the credit for one unambiguous success story: the positive impact of indigenous players across the competition. Despite comprising about 2.4 per cent of the population, in this year's national draft, indigenous players accounted for three of the first 10 picks. Vanstone is aware of the concerns about the new approach, but appears equally determined to ensure a smooth transition. But, like Dodson and Long, she cautions that it will take time to turn the statistics of disadvantage around. "If you get more kids in school, and we already have, it will take a long time for that to show up in lower mortality rates because those kids get better jobs, eat better food, have better housing and are safer. "We want improvements and we want them as soon as we can get them, but perhaps one of the mistakes of the past is to go for shorter-term announceables, rather than long-term improvements." Vanstone would like Long to reconsider the invitation to join the NIC, saying it would give him direct access to the relevant ministers and the Prime Minister. His emphatic view remains that he wants any conversation to involve elders like the Dodsons - and he was reassured by Howard's willingness to meet again. Long said he had been overwhelmed by the response of average Australians on the road. "A lot of those people who came along were affected by the issues and challenges we face." Did he feel he had achieved something, someone asked. "I've got sore feet," came the laconic reply. The walk was now over, he announced, but the nation's journey had barely begun.

|

|