Noyce work if you can get itJanuary 19 2003

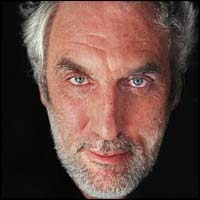

Phil Noyce tells Stephanie Bunbury about his latest movie, The Quiet American, and his plans for the future.

Phil Noyce is not likely to become a grand old man any time soon, even if he does have the size, silver hair and venerable reputation. At 52, he's full of the future. The National Film Review Board of America has just voted him the director of the year on the strength of Rabbit-Proof Fence and The Quiet American, his adaptation of Graham Greene's novel. Rabbit-Proof Fence won the AFI award for best Australian film last year and was also the top Australian film at the box office. Noyce may be jetlagged right now, his big body crumpled into a hotel armchair in South Yarra, but he's flying high. We are here to talk about The Quiet American. No surprise, really, that Noyce would leap on that story sooner or later. Greene was writing - cogently, as always, and with scary prescience - about Vietnam during the dying days of French rule in the early '50s, when it was clearly disintegrating. Noyce was part of the Vietnam generation, those who grew up with the domino theory, came to maturity as the anti-war moratoriums took over the streets and wanted to change the world. "Australians bought the domino theory hook, line and sinker," he says. "I was one of the young teenagers who trained in compulsory military service in high school, learning to avoid the Viet booby trap, and who believed, at least in the early '60s, in the validity of the domino theory. And then I saw my neighbours go off to Vietnam and, like their American counterparts, come back disillusioned. In the end, we wondered why we had been so foolish." Noyce was travelling in Vietnam in 1995 when he bought The Quiet American to read on the train. He soon realised it was "the great Vietnam war movie that hadn't been made". "It's the missing link," he says. "Because it helps us to understand why we

pursued that war so vehemently. And for the Vietnamese it is the same thing,

because they would like to know why we rained hell on them for so long ... So in

that sense, I think this is the most important of the so-called Vietnam movies.

Because it is not a film about fighting the war, so much as why we fought the

war." The world did change, at least a little, with the election of a Labor

government in 1972. The troops came home. Within three weeks, Noyce remembers,

an Australian embassy had been established in Hanoi. At home, among many other

policies that amounted to a sort of culture shock, the government put

substantial funds into fostering an Australian film industry. A new wave of

directors made films about Australia, starring Australians. At last, we could

hear actors who talked like us. Phil Noyce was one of the first. From the off, he told stories of a political

bent. His first feature, Backroads (1977), was about Aboriginal itinerant

workers. It was this film that led the writer of Rabbit-Proof Fence,

Christine Olsen, to his door more than 20 years later. "He treated the

Aboriginal people as people," she says. "Nothing more, nothing less." Then he made Newsfront (1978), now widely regarded as the best of the

New Wave films. It told the story of an old-style newsreel cameraman whose

brother goes to work for the American company that will soon squeeze out the

local product. The parallels with the fledging film industry, squeezed tight by

the Hollywood behemoth, were clear; at the same time, Newsfront was full

of characters and country that were quintessentially Australian. Noyce, who had

grown up in Griffith, understood life in the backblocks as few city slickers

did. The film breathed red dust. "The film is constructed from the newsreel footage interwoven with the

dramatic storyline," wrote playwright Hannie Rayson when a new print of the film

was given the gala treatment 20 years later. "It is a story about the tension

that exists in the Australian psyche between competing values: loyalty to family

versus the claustrophobia of suburban life, the desire for security versus the

fear of parochialism, a commitment to community life, to the 'local' versus a

yearning for challenge and new horizons ... In its day, this was a luminous

film: intelligent, ambitious in its thematic scope, honest and full of

complexity. Ironically, it now looks as quaint as the newsreels it celebrates.

But, like them, it is a record of a historical era captured on celluloid." "When you started here," says Noyce, "in the so-called New Wave, the big

thing first of all was that we had a place up on the silver screen. We were

reclaiming our history and defining our present. But making those movies, you

also felt you were part of a dialogue, part of a debate. You were financed by

taxpayers and so it was a privilege to make these stories, but there was also

this constant feedback." An industry thus took shape, but it was necessarily a small shape. Noyce soon

looked overseas for bigger challenges. The reality was that, even with

government largesse, there was not enough money in Australia to sustain whole

careers, brilliant or otherwise. "If we all stayed, the blood would be on the

carpet as we all fought each other to try to get hold of the little money that's

available. You know, we would have strangled our own babies - the next

generation of Australian film makers. For better or worse, we produce too many

film makers here, and they have to go somewhere." His 1988 film Dead Calm, the shipboard thriller that also persuaded

Tom Cruise that Nicole Kidman was a talent he should pursue, caught a few eyes

in Hollywood. He got calls. At that stage, Noyce was nearly 40. He took the

leap. For six years, he lived in Los Angeles, then moved to London for his

daughter's schooling while he went back and forth. Of course, he could see the

irony; after making the definitive film about the corruption of Australian

culture by the American machine, he was willingly oiling its evil cogs. There were, of course, dues to pay: television projects, a B-grade movie.

Then producer Mace Neufeld, who had seen and admired Dead Calm, asked him

to direct Patriot Games. After that came Sliver, then Clear and

Present Danger. He was the thriller man, perhaps because he is so phlegmatic

in life. Stars liked him; even the notoriously tempestuous Val Kilmer, who

starred in The Saint (1997), gave him no trouble. His strike rate has

also been impressive: Clear and Present Danger, for example, was

America's top-grossing film on its first weekend of release. "Working on those movies was great fun, you know," he says. "Working with

great actors, working in the studio system, watching the machine and how it

works. But it's like it's not that important how loud the explosion is, but

sometimes that is what you are concentrating on. It was certainly wonderful to

come back here and make Rabbit-Proof Fence, then continue that dialogue

with The Quiet American." Which it does, because while The Quiet American deals with the kinds

of moral uncertainties that were Graham Greene's forte - at what point do we

take sides? Is that decision to take sides ever pure? - he is also dealing

specifically with the Cold War alliance. Thomas Fowler, a world-weary English

newspaper correspondent played by Michael Caine - now a Golden Globe-nominated

performance - finds himself reporting a village massacre. Communist insurgents

lurk in every shadow. Meanwhile, the phalanxes of American aid workers and businessmen are not

quite what they seem, either. Brendan Fraser plays the quiet man of the title

with charm but a perfectly nuanced suggestion of subcutaneous fanaticism.

Greene, says Noyce, "was able to define the basic evangelistic personality that

would underpin American foreign policy from that time to this". One of the advantages of leaving Australia, Noyce says, is that with a bit of

commercial nous you can bring money back with you. The Quiet American was

a long time on the drawing board. Noyce started scouting locations back in 1995,

as soon as he had read the book, while putting out feelers to find out if anyone

had the film rights. What he was discovered was that a Swedish producer, Staffan

Ahrenberg, had bought them and then taken them to the legendary Hollywood

producer Sydney Pollack seven years earlier. They just could not raise the money

to make it, Lumet said: it was seen as "another Vietnam film". Then Noyce came along. He suggested they shoot the studio work in Australia

and the locations in Vietnam itself, rather than in Thailand or the Philippines

where previous 'Nam yarns had been shot. "It's not a cheap movie to make," says

Noyce. "Although you don't have to recreate a total war, you do have to do some,

and that's expensive. The cast was relatively small but the backdrop was very

big. When we were first trying to make it, it was budgeted closer to $US40

million." They cut it to something closer to $20 million. Not that it was plain sailing. Communication on set, with mixed Anglo and

Vietnamese crews, was never easy. And once shooting had finished, Noyce found

himself editing Rabbit-Proof Fence and The Quiet American at the

same time, running between rooms on the Fox lot in Sydney. It was madness. Then, during post-production, there were the events of September 11, 2001.

The film was tested over the next few weeks and the audience hated it.

Mall-going Americans were not ready for a film with morally compromised

characters and CIA agents destabilising other countries' governments. For months

it seemed doubtful that the film would be released at all. That's the thing about American culture, Noyce says: they go for results.

Wars have to be won. People have to be good or bad. Movies have to be sure-fire

hits. With Rabbit-Proof Fence and The Quiet American, Noyce has been

able to live in Australia for two years. "The big thing about coming back was

that it was such a relief," he says. "The films I've got planned take place here

as much as they do there. For sanity, I would certainly prefer to live in

Australia." Of course, if he decides to make a film in America, he could be off tomorrow.

But it doesn't worry him, now, that the pond is small and the films,

necessarily, must be small, too. "It's not the size of the film that matters,"

he says. "It's the size of the idea. And, arguably, you can have bigger ideas

here than in Hollywood. My personal favourite last year was Walking on

Water. What a beautiful film, what a mature film, as good as anything in any

country." Next up, he is expected to direct an adaptation of Tim Winton's Dirt

Music and, it is believed, would like Nicole Kidman and Russell Crowe in the

leads: hardly small beer. Still, it is more like a home movie than a Jack Ryan

movie, more like the films that have been telling our stories from the '70s

until now, which is what Noyce wants. "You look at those films in the AFI awards - Tracker, Australian

Rules," he says with enthusiasm. "They're not like Hollywood movies and

they're not like British movies. Every one of them has a very distinctive

Antipodean style in the way the story's told. And that comes from the much

greater freedom of expression we enjoy here." He smiles amiably. "That's my

opinion, anyway." Reprinted from the Age | |