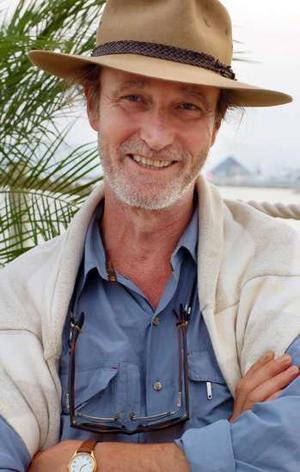

The Australian director shares a secret with Jim Schembri. EVERYBODY has their secret shame, and director Rolf de Heer has just exposed his. We're deep in conversation about Ten Canoes, his new film about love, deceit and brutal justice between two warring Aboriginal tribes in the prehistoric outback. It's a typical de Heer film in that it is unlike anything made by any other Australian filmmaker, including him. Largely improvised and spoken in the language of the Ramingining people, it was shot in the swamps of Arnhem Land and directed with Peter Djigirr, who helped ensure cultural authenticity. The film took three years and evolved through de Heer's close creative collaboration with the Ramingining. "I was the means by which they could tell their story," he says. "The film was formed by me but the content, they gave me." And of all the details de Heer wanted to include, it was the humour he was most keen to get right. "The thing I get a lot is 'I didn't realise the film would be so funny'. We are so used to this worthy approach, and our first approach was a little bit serious, a little bit reverential. But as I got deeper into it, their humour started to come through and I thought 'You can't not have this'." Some of the humour is very basic, including jokes about over-eating and farting. It almost reminds one of Adam Sandler. Then comes the bombshell. "Shamefully, I have to say to you I have never seen an Adam Sandler film," de Heer confesses. "Not that I've avoided them. I've just not got around to it." With that revelation over, de Heer wrestles with how Ten Canoes fits into the recent spate of films about indigenous culture, such as The Proposition (2005), Australian Rules, Beneath Clouds, Black and White, Rabbit-Proof Fence and de Heer's own The Tracker, (all 2002). Eventually he comes to this assessment of how Ten Canoes sits amid the canon: "In the end, it's like there is a lot of guilt involved (in those other films). So I guess where this one fits is that it's the first truly guilt-free one," he says, with a laugh. "In its story and subject matter there's nothing that allows us to connect it with white guilt." The film's recent winning of the special jury prize in Cannes helped serve the purpose of the film, which is to please the people he made it with. "Now what pleases them is that their culture is seen and recognised. So the prize at Cannes was terribly important not for me but for them because it is validation that they did great work (and that their) culture is validated in some way." The notion of indigenous people receiving cultural validation through cinema is one de Heer takes seriously. "You've got a minority culture there that has been effectively told for generations by the majority culture that their culture has no value, that it's going to disappear. So you end up with this low cultural self-esteem, which is part of what creates all the social problems. "Already the people of Ramingining feel a little bit more confident. They're a little better dealing with life, a little more able to make good decisions, and the more people respect their culture as having some value in its own right, the stronger they become, and I think that has value." De Heer remains one of Australia's most distinctive independent filmmakers. Often made on minuscule budgets, his astonishingly diverse filmography includes the sci-fi film Incident at Raven's Gate (1988), the classic black comedy Bad Boy Bubby (1993), the superb dramas The Quiet Room (1996) and Dance Me to My Song (1998), and Richard Dreyfuss' The Old Man Who Read Love Stories (2001). So how does de Heer see himself in the Australia filmmaking firmament? Simple. "I don't see myself in the Australian filmmaking firmament! What I do is I happily live in this quiet little backwater of Adelaide out of the mainstream and make films that interest me and that hopefully interest enough other people to then allow me to make the next one. "I try to take care of the process so that it's a good one, because if the process is not good then I'm wasting my life because the process is me living my life. "Then out of that come these little films, and with each and every single one of them, when they work in some way, I think 'Ahh jeez! Another fluke!' So when I'm still at the stage of thinking that every film of mine that works is a fluke, I have no sense of myself in any Australian filmmaking firmament!" Ten Canoes is now screening. | |