www.tracker.org.au |

The Answer is a Better Knowledge of History

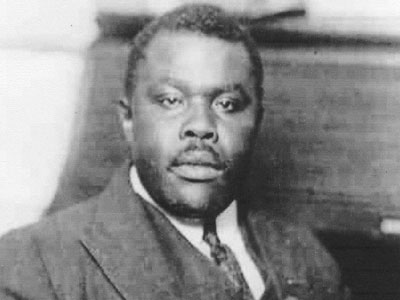

I am always being asked why it is that the Aboriginal resistance movement appears to have has lost its spark, energy and effectiveness over the past two decades. Why has the movement lost the momentum and power it had back in the heyday of the 1960s and 70s? People want from me answers as to how the malaise set in, and how we might restore or revive the glory days of old. How do we become effective again in determining the subject and nature of the debate? How do we make our voices heard again in the way we did in the past? These are reasonable and important questions. But I always point out that the answers are far from simple. To seek to answer such questions, one must first do your homework. You need to start with an analysis of history. To analyse history you need to have more than a superficial understanding of the history in question. You need to know and understand what some of the defining actions, debates and arguments have been about and how the dominant themes of those debates came to prevail today. And you need to understand the historical context and mechanics by which those debates were translated into the new Assimilationism that drives government policies today. See. I told you the answers weren't simple. Nevertheless, in this series of columns in Tracker, I shall begin to explore some of the aspects of history that we need to understand. And what aspects and interpretations of the past that we need to know if we are to try and make sense of where we are today. History and the AAPA History is important because our past defines who we are today. The history of the Aboriginal resistance helps us to know certain things about why the movement was so effective between 1920 and the mid 1980s, and why and how it was effectively suppressed by the Hawke Government. Only with an analysis of these historical issues and eras can we develop an understanding of issues today. In the early part of the Twentieth Century, certain Aboriginal activists in NSW embraced, adopted and adapted the ideas of Marcus Garvey to create the first modern Aboriginal political organisation.

The importance of these early Aboriginal followers of Marcus Garvey in the 1920s rests with their innovative adoption, adaptation and incorporation of Garvey's ideas of self-reliance and economic independence when establishing the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA) in 1925. The AAPA provided an ideological framework that derived firstly from Aboriginal cultural and social values, but which also connected with an international consciousness of anti-colonialism and self-rule. The AAPA was the first Aboriginal organisation in Australia to call for Self-Determination which included social, political, economic and land justice. That the leaders of AAPA were able to so cleverly adopt and adapt such ideas into the Australian Aboriginal context shows that they were much more sophisticated and innovative political thinkers than virtually all of their white contemporaries. But Fred Maynard, Tom Lacey and other activists of the AAPA were more than just smart thinkers. They understood the importance of grass root political organisation and began to set up numerous local branches in rural NSW, thus providing the inspiration, ground-work and example for the next generation of Aboriginal activists? that emerged in the early 1930s.. They did this by building up networks of activists in rural areas of north-east NSW and they understood the importance of maintaining good communications between their branches. Through pre-existing Aboriginal community grapevines, they created political awareness about key issues and encouraged people to become politically active. Fred Maynard's grandson, Prof. John Maynard, has pointed out that “The AAPA platform was grounded in the collective good of Aboriginal people, not the betterment of individuals”. These are examples and ideas that young budding activists of today might well examine and analyse. But these ideas were deemed subversive activities by the NSW Aboriginal Protection Board, which worked with police to monitor and undermine the work of the AAPA. Sadly, the AAPA was eventually hounded out of existence by the Protection Board by the 1930s, but it had fulfilled its task of generating widespread political awareness on many NSW Aboriginal reserves and fringe-dwelling communities and inspired the next generation of NSW Aboriginal activists. There are lessons for today in the work of the 1920s AAPA. These include the importance of building organisations from the ground up, rather than the modern fetish of building groups from the top down; to educate yourself politically, and then educate those around you; to develop and build up networks locally in your own community and then externally beyond to others and regionally; all the while building up a secure and effective communications network. Back in the 1920s activists of the AAPA were lucky if they had a horse and buggy for transport and they relied on word of mouth or letters and telegrams for communications. These days with access to mobile phones, high-tech information systems and internet social networks, the budding activists of today have an abundance of communications possibilities at their fingertips, so why isn't more happening? In my next column I will continue this exploration of the lessons to be learned from history when I look at Aboriginal resistance organisations that emerged in the 1930s -1950s, and how they are each links in a chain of resistance that continues all the way through to today.

Gary Foley

|